History & Culture

- Home

- History & Tradition

History & Tradition

The History and Culture

of the Banyankole People

In Uganda

The Kingdom of Nkore, later called Ankole, holds a significant place in Uganda’s history. Known for its rich traditions and complex social structure, it was once home to two main groups – the pastoralist Hima (Bahima) and the agricultural Iru (Bairu). Their interactions shaped the kingdom’s identity for centuries, influencing trade, culture, and power dynamics. In 1901, the signing of the Ankole Agreement formally brought the kingdom under the British Protectorate of Uganda, marking the beginning of a new chapter in its story.

- Pre-colonial Ethnic Relations in Ankole

- Royal Regalia Kingship

- Location of Ankole in Uganda

- Language of The Banyankole

- Folklore of The Banyankole People

- Religious Practices

- Traditional Clothing

- Banyankole Holidays

- Banyankole Rites of Passage

- Gender in Banyankole Society

- Ankole Traditional Houses

- Banyankole Living Conditions

- Banyankole Family Life

- Banyankole Traditional Foods

- Banyankole Education

- Banyankole Employment

- Banyankole Sports

- Banyankole Recreation

- Banyankole Crafts and Hobbies

- Banyankole Social Issues

- Banyankole Traditional Marriages

- Oruhoko

- Births

- Naming

- Political Life

- Wars in Ankole

- The Royal Regalia

- Entereko

- Method of Counting

- Death & After life Perception

Pre-colonial Ethnic Relations in Ankole

On October 25, 1901, the Kingdom of Nkore was incorporated into the British Protectorate of Uganda by the signing of the Ankole agreement.

The pastoralist Hima (also known as Bahima) established dominion over the agricultural iru (also known as Bairu) some time before the nineteenth century.

The Hima and Iru established close relations based on trade and symbolic recognition, butthey were unequal partners in these relations. The Iru were legally and socially inferior to the Hima, and the symbol of this inequality was cattle, which only the Hima could own.

The two groups retained their separate identities through rules prohibiting intermarriage and, when such marriages occurred, making them invalid. The Hima provided cattle products that otherwise would not have been available to Iru farmers. Because the Hima population was much smaller than the Iru population, gifts andtribute demanded by the Hima could be supplied fairly easily.

These factors probably made Hima-Iru relations tolerable, but they were nonetheless reinforced by the superior military organization and training of the Hima. The kingdom of Ankole expanded by annexing territory to the south and east. In many cases, conquered herders were incorporated into the dominant Hima stratum of society, and agricultural populations were adopted as Iru or slaves and treated as legal inferiors. Neithergroup could own cattle, and slaves could not herd cattle owned by the Hima.

Royal Regalia Kingship

Ankole society evolved into a system of ranked statuses, where even among the cattle- owning elite, patron-client ties were important in maintaining social order. Men gave cattle to the king (mugabe) to demonstrate their loyalty and to mark life-cycle changes or victories in cattle raiding

This loyalty was often tested by the king’s demands for cattle or for military service. In returnfor homage and military service, a man received protection from the king, both from externalenemies and from factional disputes with other cattle owners. The mugabe authorized his most powerful chiefs to recruit and lead armies on his behalf, and these warrior bands were charged with protecting Ankole borders. Only Hima men could serve in the army, however, and the prohibition on Iru military trainingalmost eliminated the threat of Iru rebellion. Iru legal inferiority was also symbolized in thelegal prohibition against Iru owning cattle.

Indeed, because marriages were legitimized through the exchange of cattle, thisprohibition helped reinforce the ban on Hima-Iru intermarriage. The Iru were also denied high level political appointments, although they were often appointed to assist local administrators in Iru villages. The Iru had a number of ways to redress grievances against Hima overlords, despite theirlegal inferiority. Iru men could petition the king to end unfair treatment by a Hima patron. Irupeople could not be subjugated to Hima cattle-owners without entering into a patron-clientcontract.

A number of social pressures worked to destroy Hima domination of Ankole. Miscegenation took place despite prohibitions on intermarriage, and children of these unions (abambari) often demanded their rights as cattle owners, leading to feuding and cattle-raiding. From what is present-day Rwanda groups launched repeated attacks against the Hima during the nineteenth century. To counteract these pressures, several Hima warlords recruited Iru men into their armies toprotect the southern borders of Ankole.

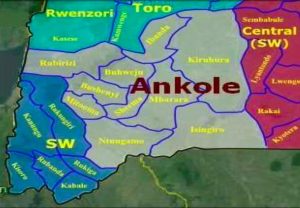

Location of Ankole in Uganda

Ankole lies to the southwest of Lake Victoria in southwestern Uganda. Sometime during or before the seventeenth century, cattle-keeping people migrated from the north into central and western Uganda and mingled with indigenous farming peoples.

They adopted the language of the farmers but maintained their separate identity and authority, most notably in the Kingdom of Ankole.

Ankole was well suited for pastoralism (nomadic herding). Its rolling plains were covered with abundant grass. Today, ideal grazing land is diminishing due to a high rate of population growth. Ankole sub-region is comprised of 12 districts, namely, Bushenyi, Buhweju, Kiruhura, Ibanda, Isingiro, Ntungamo, Mbarara, Mitooma, Rubirizi, Sheema, Kazo and Rwampara districts. People from Rujumbura and Rubando in Rukungiri District share the same culture. Originally, Ankole was known as Kaaro- Karungi and the word Nkore is said to have been adopted duringthe 17th century following the devastating invasion of Kaaro-Karungi by Chawaali, the thenOmukama of Bunyoro- Kitara. The word Ankole was introduced by British colonial administrators to describe the bigger kingdom, which was formed by adding to the originalNkore, the former independent kingdoms of Igara, Sheema, Buhweju and parts of Mpororo.

A Map of Ankole in Western Uganda

Ankole, also referred to as Nkore, is one of four traditional kingdoms in Uganda. The kingdom is located in the southwestern Uganda, specifically east of Lake Edward. Back in the day, it was ruled by a monarch known as The Mugabe or Omugabe of Ankole. The kingdom was formally abolished in 1967 by the government of President Milton Obote, & to date, it is stillnot officially restored. The people of Ankole are called Banyankole (singular: Munyankole) in Runyankole language, a Bantu language.

Due to the reorganisation of the country by Idi Amin, Ankole no longer exists as an administrative unit. It is divided into six districts: Bushenyi District, Ntungamo District, Mbarara District, Kiruhura District, Ibanda District, and Isingiro District. This former kingdom is well known for its long-horned cattle, which were objects of economic significance as well as prestige. The Mugabe (King) was an absolute ruler. He claimed all the cattle throughout the country as his own.

Chiefs were ranked not by the land that they owned but by the number of cattle that they possessed. Banyankole society is divided into a high-ranked caste (social class) of pastoralists (nomadic herders) and a lower-ranked caste of farmers. The Bahima are cattle herders and the Bairu are farmers who also care for goats and sheep. In 1967, the government of Milton Obote, prime minister of Uganda, abolished kingdoms in Uganda, including the Kingdom of Ankole.

This policy was intended to promote individualism and socialism in opposition to traditional social classes. Nevertheless, cattle are still highly valued among the Banyankole.

Language of The Banyankole

The Banyankole speak a Bantu language called Runyankole. It is a member of the Niger- Kordofanian group of language families. In many of these languages, nouns are composed of modifiers known as prefixes, infixes, and suffixes.

Word stems alone have no grammatical meaning. For example, the prefix ba -signifies plurality; thus, the ethnic group carries the name Banyankole.

An individual person is a Munyankole, with the prefix mu -carrying the idea of singularity. Things pertaining to or belonging to the Banyankole are referred to as Kinyankole, taking the prefix ki. The pastoral Banyankole are known as Ba hima; an individual of this group is referred to as a Mu hima. The agricultural Banyankole are known as Ba iru; the individual is a Mu iru.

Folklore of The Banyankole People

Legends and tales teach proper moral behavior to the young. Storytelling is a common means of entertainment. Both men and women excel in this verbal art form.

Riddles and proverbs are also emphasized. Of special significance are legends surrounding the institution of the kingship, which provide a historical framework for the Banyankole.

Folktales draw on themes such as royalty, cattle, hunting, and other central concerns of the Banyankole. Animals figure prominently in the tales.

One well-known tale concerns the Hare and the Leopard. The Hare and the Leopard wereonce great friends.

When the Hare went to his garden for farming, he rubbed his legs with soil and then wenthome without doing any work, even though he told Leopard that he was always tired fromdigging.

Hare also stole beans from Leopard’s plot and said that they were his own. Eventually, Leopard realized that his crops were being stolen, and he set a trap in which Hare was caughtin the act of stealing.

While stuck in the trap, Hare called to Fox, who came and set him free. Conniving Hare toldFox to put his own leg into the trap to see how it functioned.

Hare then called Leopard, who came and killed Fox, the assumed thief, without asking any questions.

The Banyankole recite this story to illustrate that one should not trust easily, as Leopard trusted Hare. One should also not act too quickly, as Leopard did in killing the innocent.

Religious Practices

The Banyankole’s idea of Supreme Being was Ruhanga (creator). The abode of Ruhanga was said to be in heaven, just above the clouds. Ruhanga was believed to be the maker and giver of all things. It was, however, believed that the evil persons could use black magic to interfere with the good wishes of Ruhanga and cause ill- health, drought, death or even bareness in the land and among the people.

At a lower level, the idea of Ruhanga was expressed in the cult of Emandwa. These were gods particularly to different families and clans and they were easily approachable in the event ofneed. Each family had a shrine where the family gods were supposed to dwell. Whenever beer was brewed or a goat slaughtered, a gourd full of beer and some small bits of meat were put in the shrine to the Mandwa. In the event of sickness or misfortune, the family member swould perform rituals called okubandwa as a way of supplicating the gods to avert sickness or misfortune. The majority of Banyankole today are Christians. They belong to major world denominations, including the Roman Catholic Church, or the Church of Uganda, which is Anglican.

A South Ankole Diocese Bishop Conforming Young Christians

Fundamental Christianity, such as Evangelicalism, is also common. Public confessions of such sins as adultery and drunkenness are common, as well as rejection of many traditional secular and religious practices.

The element of indigenous Kinyankole religion that survives most directly today is the belief in ancestor spirits. It is still believed that many illnesses result from neglect of a dead relative, especially a paternal relative.

Through divination it is determined which ancestor has been neglected. Presents of meat or milk and/or changes in behavior can appease the ancestor’s spirit.

Traditional Clothing of The Banyankole People

Dress differentiates Banyankole by rank and gender. Chiefs traditionally wore long robes of cowskins. Ordinary citizens commonly were attired in a small portion of cowskin over their shoulders. Women of all classes wore cowskins wrapped around their bodies.

They also covered their faces in public. In modern times, cotton cloth has come to replace cowskins as a means of draping the body. For special occasions, a man might wear a long,white cotton robe with a Western-style sports coat over it.

A hat resembling a fez may also be worn. Today, Banyankole wear Western-style clothing. Dress suitable for agriculture such as overalls, shirts, and boots are popular. Teenagers are attracted to international fashions popular in the capital city of Kampala.

Major Holidays of the Banyankole People

The majority of Banyankole celebrate Christian holidays, including Christmas (December 25) and Easter (in March or April).

The Banyankole Peoples’ Rites of Passage

Traditionally, in early childhood, children began to learn the colors of cows and how to differentiate their families’ cows from those of other homesteads. Boys were taught how to make water buckets and knives.

Girls were taught how to make milk-pot covers and small clay pots. By seven or eight yearsof age, boys were taught how to water cattle and calves. Girls helped by carrying and feeding babies. They were also expected to wash milk-pots and churn butter.

Among the Bahima (the herders), girls began to prepare for marriage as early as eight yearsof age. They were kept at home and given large quantities of milk in order to grow fat. Today, heaviness is still valued.

Among the Banyankole, the father’s sister was (and still is) responsible for the sexual morality of the adolescent girl. Nowadays schools, peer groups, popular magazines, and other mass media are rapidly replacing family members as sources of moral education for teenagers.

Traditionally, adulthood was recognized through the establishment of a family by marriage. The acquisition of large herds of cows for Bahima and of abundant crops for Bairu (farmers)were other markers of adulthood. Full adult status was achieved through the rearing of a large family.

Gender issues among the Banyankole

Social relations among the Banyankole cannot be understood apart from rank. In the wider society, the Mugabe (king) and chiefs had authority over herders (Bahima).

The Bahima had authority over the Bairu (farmers). Within the family, husbands had authority over wives, and older children had authority over younger ones. Inheritance typically involved the eldest son of a man’s first wife, who succeeded to his office and property.

Relations between fathers and sons and between brothers were formal and often strained. Mothers and their children, and brothers and their sisters, were often close.

Social relations in the community cantered around exchanges of wealth, such as cows and agricultural produce.

The most significant way that community solidarity was and still is expressed is through the elaborate exchange of formalized greetings. Greetings vary by the age of the participants, the time of day, the relative rank of the participants, and many other factors. Anyone meeting an elder has to wait until the elder acknowledges that person first.

Ankole Traditional Houses

The milk house for the Bahima was the central house and it organised the homestead, it is where most activities took place, visitor entertainment, milk storage, ghee making, storytelling among others. The unmarried sons House had to be next to the kraal for the cattle’s security.

The toilet and bathroom were in the backyard outside the surrounding hedge for privacy and were oriented facing uphill away from the homestead hedge. Bahima house is a round mud wall with cone thatch roof. It consisted of mainly two spaces, back room & the living room.

General Living Conditions of The Banyankole

The Mugabe’s (king’s) homestead was usually constructed on a hill. It was surrounded by a large fence made from basketry. A large space inside the compound was set aside for cattle.

Special places were set aside for the houses of the king’s wives, and for his numerous palace officials. There was a main gate through which visitors could enter, with several smaller gates for the entrance of family members.

Traditionally, the Bahima (herders) maintained homes modelled after the king’s but much smaller. The Bairu (farmers) traditionally built homes in the shape of a beehive. Poles of timber were covered with a framework of woven straw. A thick layer of grass frequently covered the entire structure.

Today, housing makes use of indigenous materials such as papyrus, grass, and wood. Homes are primarily rectangular. They are usually made from wattle and daub (woven rods and twigs plastered with clay and mud) with thatched roofs. Cement, brick, and corrugated iron are used by those who can afford them.

Family Life of The Banyankole People

Among the Bahima, a young girl was prepared for marriage beginning at about age ten, though sometimes as early as eight. Marriages often occurred before a girl was sexually mature, or soon after her initial menstruation. As such, teenage pregnancies before marriage were uncommon, and pre-marital virginity was highly valued.

Polygyny (multiple wives) was associated with rank and wealth. Bahima herders who were chiefs typically had more than one wife, and the Mugabe (king) sometimes had over one hundred. Marriages were alliances between clans and large extended families. Among both the Bahima and the Bairu, pre-marital virginity was valued.

Today, Christian marriages are common. The value attached to extended families and the importance of having children have persisted as measures of a successful marriage.

Monogamy is now the norm. Marriages occur at a later age than in the past, due to the attendance at school of both girls and boys. As a consequence, teenage pregnancies out of wedlock have risen.

Girls who become pregnant are severely punished by being dismissed from school or disciplined by parents. For this reason, infanticide is now more common than in the past, given that abortion is not legal in Uganda.

Special Foods of the Banyankole People

Bahima herders consume milk and butter and drink fresh blood from their cattle. The staple food of a herder is milk. Beef is also very important. When milk or meat are scarce, millet porridge is made from grains obtained from the Bairu. Buttermilk is drunk by women and children only. When used as a sauce, butter is mixed with salt, and meat or millet porridge is dipped into it.

Children can eat rabbit, but men can eat only the meat of the cow or the buffalo. Herders never eat chicken or eggs. Women consume mainly milk, preferring it to all other foods.

Cereals domesticated in Africa millet, sorghum, and eleusine dominate the agricultural Bairu sector. The Bairu keep sheep and goats. Unlike the herders, the farmers do consume chickens and eggs.

Education for The Banyankole People

attending a Class Lesson

In the past, girls and boys learned cultural values, household duties, agricultural and herding skills, and crafts through observation and participation.

Instruction was given where necessary by parents; fathers instructed sons, and mothers instructed daughters. Elders, by means of recitation of stories, tales, and legends, were also significant teachers.

Formal education was introduced in Uganda in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Today, Ankole has many primary and secondary schools maintained by missionaries or the government. In Uganda, among those aged fifteen years and over, about 50 percent are illiterate (un able to read or write). Illiteracy is noticeably higher among girls than among boys. Teenage pregnancy often forces girls to end their formal education.

Schools in Ankole teach the values and skills needed for life in modern-day Uganda. At the same time, schools seek to preserve indigenous (native) Ankole cultural values. The Runyankole language is taught in primary schools.

All schools have regular performances and competitions. They involve dances, music, and plays. Where appropriate, instruction also makes use of Ankole folklore and artistic expression.

Employment for the Banyankole

Cattle Keeping

Among the Bahima, the major occupation was tending cattle. Every day the herder travelled great distances in search of pasture. Young boys were responsible for watering the herd. Teenage boys were expected to milk the cows before they were taken to pasture.

Women cooked food, predominantly meat, to be taken daily to their husbands. Girls helped by gathering firewood, caring for babies, and doing household work. Men were responsible for building homes for their families and pens for their cattle.

Among the Bairu, both men and women were involved in agricultural labour, although men cleared the land. Millet was the main food crop.

Secondary crops were plantains, sweet potatoes, beans, and groundnuts (peanuts). Maize(corn) was considered a treat by the children. Children participated in agriculture by chasing birds away from the fields.

Sports Life of The Banyankole People

Sports, such as athletics and soccer, are very popular in primary and secondary schools. Children play an assortment of games including hide-and-seek, house, farming, wrestling, and ball games such as soccer. Ugandan national sporting events are followed with great interest in the Ankole region, as are international sporting events.

Recreation of The Banyankole People

Radio and television are important means of entertainment in Ankole. Most homes contain radios that have broadcasts in English, Kiswahili (the two national languages), and Runyankole. Books, newspapers, and magazines also are popular.

Social events such as weddings, funerals, and birthday parties typically involve music and dance. This form of entertainment includes not only modern music, but also traditional forms of songs, dances, and instruments.

The drinking of alcoholic and non-alcoholic bottled beverages is common at festivities. In the past, the brewing of beer was a major home industry in Ankole.

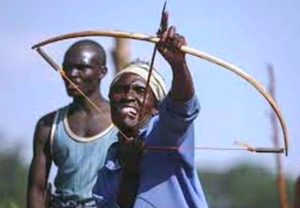

Crafts and Hobbies of the Banyankole

for hunting

Carpenters, ironworkers, potters, musicians, and others were once permanent features of the Mugabe’s (king’s) homestead or were in constant contact with it. Carpenters fashioned stools, milk-pots, meat-dishes, waterpots, and troughs for fermenting beer.

Ironsmiths manufactured spears, knives, and hammers. Every family had a member who specialized in pottery. Pipes for smoking displayed the finest artistic creativity. Small, colored beads were used to decorate clay pipes, which came in various shapes and sizes, and walking sticks.

Traditional industries are not nearly as significant as in the past. Nevertheless, one can still observe the use of traditional pipes, water-pots for music, decorated walking sticksexchanged at marriage, and the use of gourds and pottery.

Social Problems of the Banyankole People

among the Banyankole

Milton Obote ruled Uganda from 1962 until 1971, when he was overthrown by Idi Amin. Obote prohibited the formation of ethnic kingdoms within Uganda. During Idi Amin’s dictatorship in the 1970s, all Ugandans suffered from political oppression and the loss of life and property. Obote once again took over in 1980 after the overthrow of Amin and ruled oppressively.

Resistance to Amin and Obote resulted in the destruction of towns and villages. Uganda is currently working toward economic recovery and democratic reform.

Since the mid-1980s, AIDS has been a serious problem. As adult Ugandans die of AIDS, many children become orphans. There has been a strong national effort to educate the public through mass media about AIDS prevention.

A growing population, in spite of AIDS, remains a threat to a pastoral way of life. Warfare in neighboring countries such as Rwanda has contributed to population growth, as refugees have regularly come into the region.

Traditional Marriages among The Banyankole People

(Okwanjura/Okuhingira)

The Banyankole of South-Western Uganda are known for their culture-rich marriage; the Kuhinjira. Kuhinjira is a gift giving pre-wedding ceremony of the Bafumbira Tribe from southwestern Uganda. The brides’ family gives gifts to the grooms’ family.

The common thread in the Ankole marriage like many African traditional marriages is to create closeness to the bridal family.

For example, among the Bahima-Banyankole, the aunties and uncles give cows to the bride during the kuhingira.

Younger girls and boys called the enshagarizi then escort the bride to the groom’s place after the blessings from the elders. Today, the groom’s side has to organise the transport for these people because they are very important for any marriage ceremony in Ankole.

Going back is not necessarily the role of the bridegroom. After the kuhingira, the bride’s side is still in control though. The bride according to the culture is not supposed to do any work until the cultural initiation.

This is done after about ten days from the giveaway day. During this initiation, the bride is made to light fire in the kitchen in the tradition called okukoza omumuriro (helping the bride to start toughing fire). Because of modernity however, some brides have left the bridal room (orusika) the day after marriage to continue looking for a living in the competitive world where every minute lost contributes a lot to poverty in the homes. Many people in Uganda may find it hard to understand the Ankole culture and language butmany know the words okwanjura, okushwera and okuhingira irrespective of the language they speak.

Oruhoko

Okuteera oruhoko was a phrase used to describe the practice whereby a boy whom the girls had deliberately refused to love or whom a particular girl had rejected could force the girl to marry him abruptly without her consent and much preparation.

The practice of okuteera oruhoko was characteristic of the traditional Ankole society but vestiges of it still appear. Society decried this practice, but it was common and helpful, nonetheless. However, the offender had to be fined by paying a big bride wealth. There were various ways in which this practice was carried out.

One such ways was by using a cock. A boy who had desired and wished to marry a girl who had rejected him, would get hold of a cock, go to the girl’s homestead, throw the cock in the compound, and ran away. The girl had to be whisked to the boy’s home immediately because it was believed and feared that should the cock crow when the girl was still at home, refusing to follow the boy or making unnecessary preparations, she or somebody else in the family would instantly die.

Another type of Oruhoko was done by smearing millet flour on the face of the girl. If the boy chanced to find the girl grinding millet, he would pick some flour from the winnowing tray usedto collect the flour as it comes off the grinding stone and smear it on the girl’s face. The boy would run away, and swift arrangements would be made to send him the girl as any delaysand excuses would cause consequences similar to those methods described above.

Among the Bahima especially, there were three other ways in which the okuteera oruhukowould be done. One of them was for the boy to put a tethering rope around the neck of the girland then pronounce in public that he had done so. The second one was to put a plant known as orwihura on the girl’s head; and the third one was for the boy to sprinkle milk on the girl’s face while milking. It should be pointed out that this practice was only possible if the girl and the boy were from different clans.

Oruhuko was a dangerous and degrading practice. It was usually tried by boys who failed to have alternatives. If the boy was not lucky enough to elude and run faster than the relatives of the girl, it was however usually done so abruptly that before the girl’s relatives could get organized, the boy would have disappeared. The punishment was usually inflicted on the boy through the payment of too much bride wealth. He would pay double or normal charge or even more. The extra cows which were charged were not refunded if the marriage broke up.

Births

The Banyankore did not have peculiar birth customs. Usually when a woman was to give birth for the first time, she would be sent to her mother. Brave women, and majority of them werebrave, could give birth by themselves without any need for a midwife. However, if things went wrong, an acting midwife, usually an old woman would be summoned.

If the afterbirth refused to come out freely and quickly after the child, some medicine would be administered to the woman. If the normal herbs failed to induce it out, the husband of the woman was required to climb with a mortar to the top of the house, raise an alarm and slide the mortar down from the top of the house.

Naming

The child could be named immediately after birth. The normal practice was after the mother had finished the days if confinement referred to as ekiriri. The woman would confine herself or four days of the child was a boy and three days if the child was a girl. After three or four days, as the case may be the couple would resume their sexual relationship in a practice known as okucwa eizaire.

The name given to the child depended on the personal experience of the father and the mother, the time when the child was born, the days of the week, the place of birth, or the name of an ancestor. The name would be given by the father, the grandfather, and the mother of the child. However, the father’s choice usually took precedence.

The names given were verbs or nouns that could appear in normal speech. Often the names also portrayed the state of mind of the persons who gave them. For example, the name Kaheeru among the Banyoro portrayed the fact that the husband suspected that the woman got the child outside the family. In traditional Ankole, it was normal for the woman to have sex with her in-laws and even have children by them. Such children were not regarded any differently from the other children in the family.

Political Life of The Banyankole

The Banyankole had a centralized system of government. At the top of the political ladder, there was a king called omugabe. Below him there was a prime minister known as Enganzi. Then there were provincial chiefs known as Abakuru b’ebyanga. Below them, there were chiefs who took charge of local affairs at the parish and sub-parish levels.

The position of the king was hereditary. The King had to belong to the Bahinda royal clan who claimed descendant from Ruhanga, son of Njunaki. Whenever a King died, there were often succession disputes to determine who would succeed to the throne. Thereafter, there would be an elaborate ceremony to install the new King. Whenever a king died, some of his wives would commit suicide or they would be forced to do so.

Some of the servants in the royal court would also commit suicide. It is said that in the earlier times, some people of the Baingoclan would also be killed in order to accompany the King in the afterworld. The corpse of theking was also known as omuguta to distinguish it from that of an ordinary person which was known as omurambo. It was specially buried by the Bayangwe clan styling themselves for the occasion as the Abahitsi.

To communicate the message that the King had died, one would not say the t Omugabe afire which is the appropriate Runyankole term, rather one would say that Omugabe ataahize.

Wars in Ankole

The Kingdom had a standing army. The army was divided into battalions known as emitwe (singular omutwe). Each battalion was under a province known as Mukuru w’ ekyanga sometimes referred to as Omukungu. Often, the kingdom of Nkore was a war with the neighboring states and sometimes she sent raiding expeditions to Karagwe and Buhweju.

The Kingdom of Bunyoro sometimes raided Nkore and took away a lot of cattle. Notable among the Banyoro invasions of Nkore were those of Omukama Olimi I during the reign of Ntare I Nyabugaro and that of Omukama I Walimi in the 17th century during the reign of Ntare IV Kitabanyoro. During the reign of Ntare IV, there occurred another war between the Banyankole and the Nkondami (soldiers) of Kabaundami of Buhweju.

During the reign of King Machwa after the death of Ntare IV, an expedition was sent against Irebe, the King of Bwera. The expedition brought a lot of plunder among which were cattle and Irebe’s sacred circlet, Rutare, which was thereafter used by the Bagabe of Nkore in making rain. Another invasion of Nkore took place during the reign of Kahaya I Nyamwanga. The invasion was by the Banyarawanda under the King Kigyeri III Ndabarasa.

The Royal Regalia

The royal regalia of Ankole consisted of a spear and drums. The main instrument of power was the royal drum called Bagyendanwa. This drum was believed to have been made by Wamala, the last Muchwezi ruler. This drum was only beaten at the installation of a new King. It had its special hut, and it was considered taboo to shut the hut. A fire was always kept burning for Bagyendanwa and this fire could only be extinguished in the event of the death of the King. The drum had its own cows and some other attendant drums namely, kabembura, Nyakashija, eigura, kooma and Njeru ya Buremba which was obtained from the kingdom of Buzimba.

Entereko

The Banyankole brewed beer by squeezing ripe bananas and mixing the resulting juice with water and sorghum and then letting the mixture ferment overnight in a wooden trough called obwato. Beer was required at every social communal work or any other function.

Whenever beer was made, the Banyankole had what they called entereko. If someone brewed beer, he had to reserve some for the neighbors as a sign of belonging and good neighborliness. This beer so reserved was known as entereko.

Normally, one or two days after someone had brewed beer, he would call his neighbors and serve then the reserved beer. This practice was so important that anyone who failed to comply with it was considered a bad neighbour. He would not be accorded the services of the neighbors in the event of need.

During the service of the entereko, the men would discuss important matters of substance that affected their area in particular, the kingdom and beyond. There would be a lot of merry making including dancing. The traditional dance among the Banyankore was called ekyitaguriro and men and women would participate in it. The Bahima also sang and made competitive recitals connected with valor in wars of offences and defense and about cattle.

The staple food of the Banyankole was millet. It was supplemented with Bananas, potatoes, and cassava. A rich and prosperous family was judged by its ability to maintain food supplies throughout the year.

The main sauces were beans, peas, and ground nuts plus a variety if greens such as eshuwiga, enyabutongo, dodo, ekyijamba, omugobe, omuriri and some others as well as meat of both domestic and wild animals.

A family that could not produce or store enough food to sustain itself for most of the year wasnot respected. In times of shortages, a woman and her daughters would go and work for food by digging in another family’s garden. This practice was called okushaka. It was very degrading and brought shame on the family concerned. Moreover, this would result in the daughters of the family failing to attract would-be suitors because it would be well known in the area that they belonged to a lazy home.

Millet and meat were prepared for important occasions. Potatoes and cassava were not respectable foods and unless there was a real shortage of food, they could not be presented to a visitor or to be eaten. It was rear for a family to eat and finish the whole meal. However, the family head was not supposed to eat leftovers. Besides men and boys were advised not to eat a burnt potato. The reason was that it was so sweet that whenever a man remembered its sweetness while on a hunt or work, he might be tempted to leave his duties and come back home. Such food was eaten by women and children. The main food of the Bahima was milk ad blood called enjuba. They would, in addition barter potatoes, cassava, and matooke from the agriculturalists in exchange for milk and ghee. In times of real scarcity, the Bahimacould just subsist on milk and blood.

Method of Counting

The Banyankole had their own method of counting. They could count from one to ten using fingers. One was indicated by showing only the fore finger. Two was indicated by showing their first and second fingers, three was indicated by raising the last and the third fingers one one’s hand, and five was counted by clenching the fist with the thumb enclosed. Six was indicated by showing the first, second and third fingers. Seven was implied by holding down the third finger and showing the first, middle and last fingers. Eight was implied by snapping the first fingers of both hands, nine was indicated by clenching the middle finger with the thumb and clenching the fist with the thumb outside meant ten.

Death and After life Perception

The Banyankole did not believe that death was a natural phenomenon. According to them, death was attributed to sorcery, misfortune, and the spite of the neighbors. They even had a saying: Tihariho mufu atarogyirwe. Meaning; “there is no body that dies without being bewitched”. They found it hard to believe that a man could die if it was not due to witchcraft and malevolence of other persons.

Moreover, after every death, the persons affected would consult a witch doctor to detect whoever was responsible for causing the death.

A dead body would normally stay in the house for as long as it would take all the important relatives to gather. Among the Bairu, a person would be buried either in the compound or in the plantation. Among the Bahima he would be buried in the kraal. Burial was usually done in the afternoon and the bodies were buried facing the east. A woman was made to lie on her left while a man was made to lie on his right. After burial, a woman was accorded three days of mourning whilea man was accorded four days.

During the days of mourning, all the neighbors and the relatives of the deceased would remain camping and sleeping at the home of the deceased. During this period, the whole neighborhood would not dig or do manual work because it was believed that if anyone dug, or did manual work during the mourning days, he would cause the whole village to be ravaged by hailstorms.

Such a person could also be regarded as a sorcerer and could easily be suspected of having caused the death of the person who had just been buried. However, the abstinence of the neighbors from digging and doing manual work was meant to console the relatives.

If the dead man was the head of the household, his leading bull would be killed and eaten to end the days of mourning. Further ritual ceremonies would be conducted if the dead man was very old and had grandchildren. If a person died with a grudge against someone in the family, he was buried with some objects to keep the spirit occupied so that it would fail to have time to haunt those with whom the deceased had a grudge.

There were special burials for spinsters and those who committed suicide. It was considered taboo for one to commit suicide. The burial of one who committed suicide was very complicated. The body would be cut from a tree by a woman who had attained menopause (encurazaara). Such a woman was heavily fortified with charms. Indeed, it was believed that whoever performed the role of cutting the rope used by the suicide would soon die also.

Tradition has it that at times; the corpses of suicide victims could not be touched. A grave was dug directly under the corpse so that when cutting the rope, the corpse would fall into the grave. The grave was then covered and that was all. There would be neither mourning nor the normal funeral rites. The tree on which the victim has hugged himself would be uprooted and burnt. The relatives of the suicide victim would not use any piece of that tree for firewood.

There were also particular formalities for the burial of a spinster. If such a girl died, it was feared that her spirits would come back to haunt the living simply because her girl had died unsatisfied. In order to placate the spirit and avert its evil retributions, before the body was taken for burial, one of the brothers of the dead girl was required to pretend making love with the corpse. This act was known as okugyeza empango ahamutwe. Then the body was passed by the rear door and buried. It is said that if a man died unmarried, he would be buried with a banana stem to occupy the position of the supposed wife. This was believed to propitiate the dead man’s spirit and its evil retributions on the living. The body was also passed through the rear door.

Among the Banyankole illness is not considered a natural cause of death; therefore, such deaths require an investigation to find the responsible party.

By contrast, old age is accepted as a sufficient cause for death. It is held that God allows old people to die after the completion of their time on earth. The Banyankole view death as a passage to another world. When a man dies, every relative, along with friends and neighbors, is informed.

A person who fails to attend the funeral without a good reason may be suspected of being associated with the death. Before burial, the body is washed, and the eyes are closed.

As the deceased is placed in the grave, the right hand is placed under the head while the left hand rests on the chest. The body lies on the right side.

One or more cows are slaughtered to feed everyone present. Beer is provided as part of the mourning. The mourning goes on for four days. A deceased woman is treated in a similar manner except that in the grave she is made to lie on the left side as if she were facing her husband.